Modern Civilization is Irrational

Modern civilization is based on rationality, but it is not rational.

Most people think of modern civilization as an expression of rationality, or even as excessive rationality. They see the complex, highly abstract theories of modern science, the complex and carefully designed modern technology that we depend on, and the highly efficient and carefully managed industrial processes that produce everything from toothpaste to cars to hamburgers. Modern civilization seems like a triumph of rationality. The market and the printing press unleashed rationality, and a wave of intellectual progress created the modern world.

That story is true, but incomplete.

Each part of modern civilization is rational in itself, within its bounds. A lot of careful thought goes into the design of a car, a dishwasher or a skyscraper. They aren’t as well-designed as they could be, but they are carefully thought-out. They are also based on empiricism. Knowledge accumulates, and is applied to new problems. The designs of cars, dishwashers and skyscrapers are tested, and errors are corrected. Modern technology depends on logic and empiricism.

However, modern civilization as a whole was not designed. It just happened.

Every part of modern civilization was created by human choices: every road, every bridge, every car, every dishwasher, every building, every computer, every circuit on a computer chip, etc. Each part is rational in itself, because it was rationally designed and selected. But modern civilization as a whole was not rationally designed or selected.

The aggregate structure of millions of designs is not a design. The aggregate effect of millions of choices is not a choice. The rationality of the parts does not imply the rationality of the whole.

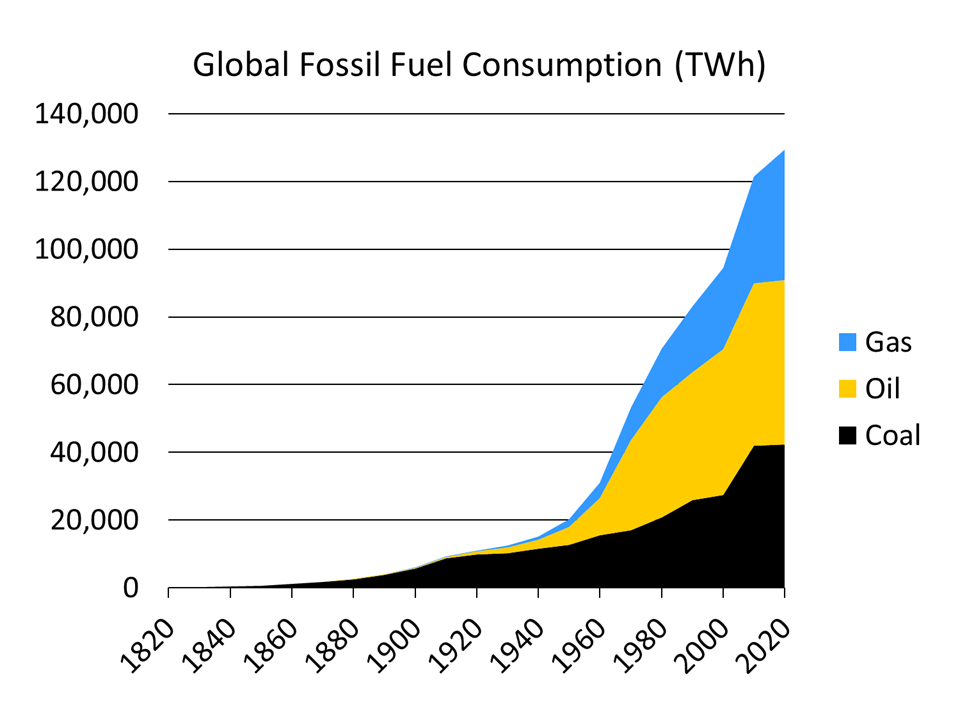

Modern civilization emerged by an amplifying feedback loop. The growth of civilization is driven by many individual human desires and actions. But civilization needs energy to grow. Modern civilization is powered by fossil fuel energy. As modern civilization expanded on the scales of population, economy and complexity, it was able to extract and use more fossil fuel energy. Growth enabled more growth.

Source: Our World in Data

Modern civilization is like a forest fire. Fossil fuels existed in the Earth’s crust for millions of years. That carbon eventually “found a way” to burn. We could say, metaphorically, that it wants to be oxidized. Modern civilization is a very complex fire, which consumes fossil fuels. Like a forest fire, it finds more fuel as it expands. The bigger the forest fire, the bigger its margins, and the faster it can grow. But it runs out of fuel eventually. The same is true of modern civilization. The bigger it gets, the more fossil fuels it can extract from the ground. However, the supply of fuel is not infinite. Eventually, the fire will burn itself out.

It may seem strange to think of modern civilization in this way. We normally think of cars, dishwashers, buildings, roads and computers as serving our desires, not as a way to oxidize carbon. We believe that we are using the carbon, not vice versa. But the system as a whole has been selected to oxidize carbon. Our desires are instrumental to that process. In a sense, we were created by the carbon to have those desires, and to drive the process. Carbon found us, and is using us.

It is a metaphor. But it is a useful change of perspective. It is no less accurate, and in some ways more accurate, than thinking of modern civilization as a human creation that serves our desires.

Again, we didn’t design modern civilization. It just happened.

Consider a dishwasher. The form of a dishwasher has been designed and selected to satisfy human desires. First, it was designed by an engineer to solve a problem: washing dishes. It was also designed to be relatively cheap and easy to produce. Next, it was selected by the market. To become a successful product, a dishwasher must appeal to consumers. It must also generate a profit for the producer. Finally, a dishwasher is controlled by its human user. It has buttons and dials that determine what it does. The form of a dishwasher has been designed and selected to solve human problems, and it is an instrument of human will.

None of that applies to modern civilization. It was not designed by human intellect. It was not selected to satisfy human desires. It is not controlled by human will. Thus, it is not rational.

We could try to make our civilization rational. That would require:

- Understanding our civilization and the historical processes that created it.

- Defining a long-term, collective purpose for our civilization.

- Designing a civilization to attain that purpose.

- Acting together on a global scale to make the design real.

Whenever I propose that we take control of our destiny in this way, idiotic right-wingers start shrieking like little girls about “globalism”, “totalitarianism”, “NWO”, “WEF”, etc. Their implicit assumption is that we can trust nature/history, so we shouldn’t try to design civilization or choose our collective destiny.

They fear the unintended consequences of action. But inaction also has unintended consequences.

Nature/history is not on our side. It doesn’t give a rat’s ass about us. Without action, we are almost certainly doomed.

It might seem like history is on our side, because (for now) we are history’s winners. But that’s inevitable, due to the anthropic principle. Looking backward, it will always seem like history is on our side. Otherwise, we wouldn’t be here to look backward. Looking forward, however, nature/history is not on our side. We need to be clever or lucky to be winners in the future.

Our civilization is a runaway growth process, not a magical pony-ride to utopia. If we don’t control it, then it will simply burn through its fuel and collapse, leaving behind literal and metaphorical ashes. We can take control of our destiny, or we can be instruments of carbon oxidization.